When does an “object” become a market asset, and when does it remain merely a keepsake?

The collectors’ market has long ceased to be limited to paintings, sculpture, and porcelain displayed in cabinets. Increasing amounts of capital – and increasingly informed demand – are flowing toward objects “beyond art”, that is, items that originally had a utilitarian, technical, or advertising function, or were simply part of everyday life. For many owners this still comes as a surprise: a ticket, a box, a poster, a camera, an old toy, an ignition clock, an enamel sign, a complete set of labels, or an element of a ship’s or hotel’s equipment can achieve prices that would be unthinkable in a traditional antiques shop. At the same time, the vast majority of similar objects have no particular value at all. What, then, determines that one example enters the premium collectors’ circulation while another remains merely a “nice old thing”?

The professional market is just as selective here as it is in fine art: it does not pay for sentiment, but for rarity, condition, completeness, provenance, and above all for demand. Importantly, demand in these categories can be more dynamic than in traditional antiques, because it is linked to fashion, popular culture, generational nostalgia, and to what the market recognizes as an “icon of an era.”

“Extra-museum” collecting: what this category includes

In practice, collectible objects beyond art form a broad ecosystem that includes, among others:

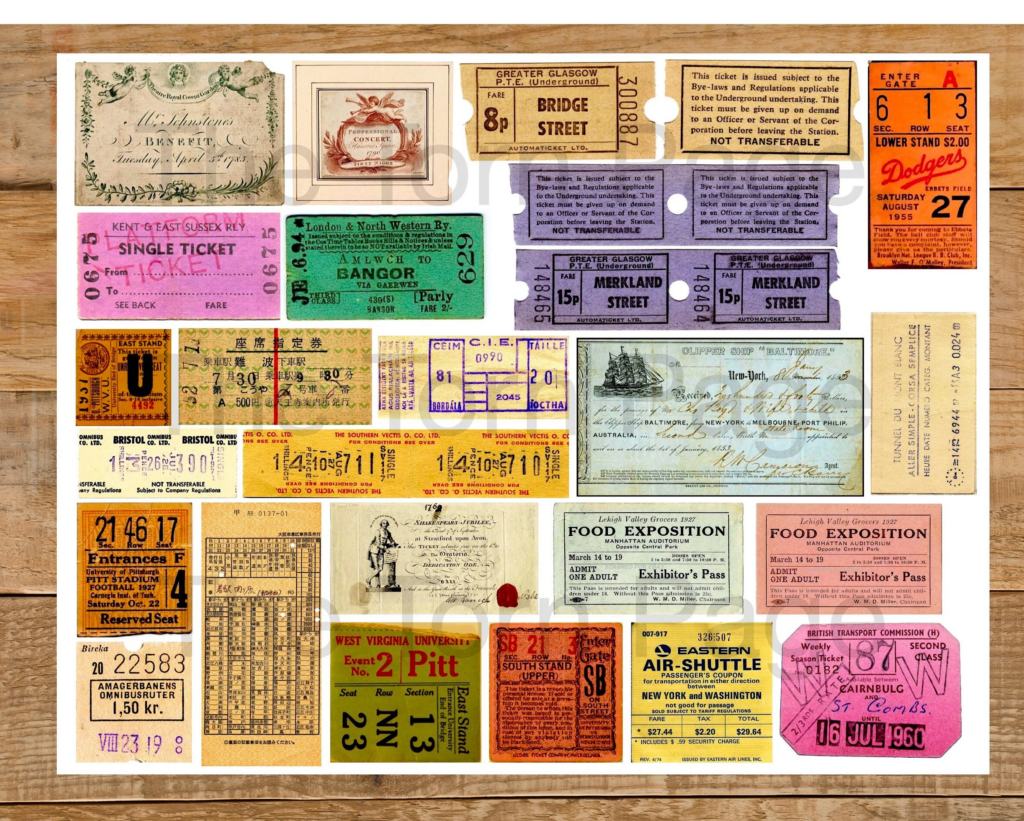

- memorabilia and ephemera: tickets, posters, leaflets, invitations, catalogues, tags, packaging, manuals, advertisements,

- utilitarian design: household equipment, radios, cameras, telephones, lighting, interior fittings,

- technology and industrial history: tools, devices, measuring instruments, elements of railway, automotive, and aviation history,

- pop-culture collectibles: toys, figurines, games, comics, film, music, and sports memorabilia,

- advertising and enamel objects: signs, lightboxes, tins, display cases, display stands,

- thematic collections: tobacco, perfumes, pharmacy, photography, watchmaking, tourism, hospitality,

- militaria and “material history” (where legality and provenance are beyond dispute).

They are united by one feature: they were often created as consumable objects, and therefore survived less frequently than works of art. Rarity combined with demand can thus build value faster than in traditional segments.

Rarity does not mean “old”: what supply is really about

Owners often say: “it is 70 years old, so it must be expensive.” The market responds differently: how many such objects actually exist, and in what condition? In this category, age is only a secondary variable. Two concepts are crucial:

- objective rarity: few were produced or few survived,

- market rarity: even if more examples exist, they appear for sale only sporadically.

A typical example is documentation. The instruction manual, box, tag, and complete set of inserts are often harder to obtain than the product itself. This is precisely why, in extra-museum collecting, completeness functions as a currency.

Condition: in this category it is unforgiving

If in classical antiques patina can be an advantage, then in pop-culture, advertising, and technical objects the market often expects something else: clarity, absence of losses, original surfaces, complete graphics, intact corners, and unpainted lettering.

For posters and paper, what matters is: no folds, abrasions, stains, reinforcements, or “emergency” repairs.

For enamel: no chips, no secondary lacquers, no aggressive cleaning.

For toys: completeness, no cracks, no “refreshing”, original paints and decals.

For technology: completeness of components, no mixed parts, original markings.

The market rewards objects that “defend themselves” by their condition, because quality is immediately visible.

Originality and “firstness”: editions, series, versions

In collectible objects beyond art, concepts familiar from watches or design are of enormous importance: first series, first version, variants, short production runs, manufacturing errors, limited editions. These elements often create the premium segment. Differences may be minimal – lettering colour, typeface, marking on the underside, mould number, packaging version – but for the market they are decisive. That is why professional valuation begins with identification: what exactly is it, and which version does it represent? Without this, the object remains merely “similar to.”

Provenance: when history works, and when it does not matter

In objects beyond art, provenance can operate in two distinct ways. It increases value when it:

- confirms authenticity and date (receipts, documentation, archival photographs),

- links the object to a specific place (hotel, airline, industrial plant, stadium),

- indicates a significant owner or event,

- builds credibility (especially in film and sports memorabilia).

It has little significance when the object is common and the market buys it for condition and appearance alone. One must also remember the risk: in fashionable categories it is easy to fabricate secondary stories, and the market is particularly vigilant here. History helps only when it is verifiable.

Culture, nostalgia, and demand cycles: this segment moves faster

Objects beyond art are especially susceptible to waves of demand. A generational mechanism is at work: people buy what was an icon of their childhood, youth, or family home. Later the market matures; some items increase in value, others fade. Therefore, valuation must consider not only the object itself, but also the state of the market: whether the category is currently sought after, whether demand is temporary or structural, whether it is international or local, and whether it functions at auctions or only in private offers.

Asking price is not value: the most common owners’ trap

In these categories the internet is full of inflated offers that never sell. The market values objects according to comparable transactions, not according to the seller’s ambitions. Professional valuation begins with a simple question: for how much do similar examples actually sell, in what condition, and where?

Conclusion: the market pays for defensibility, not for a “curiosity”

Collectible objects beyond art can be market-wise stronger than classical antiques, but only when they meet a strict set of conditions: they are rare or rarely available, they are in premium condition, they are correctly identified (version, series, completeness), and demand is real and measurable through transactions. Everything else – even very “old” – remains merely a keepsake.