When does ceramics cease to be utilitarian and begin to be collectible? (ceramic studios, editions, signatures)

Ceramics in the twentieth century made a move that the market long struggled to name: from a material of everyday life it became an artistic medium. For decades it was treated as a “nice object for interiors” – a cup, a vase, a platter – while some creators were already building a language comparable to sculpture and printmaking, only in clay and glaze. Today, as auction houses and galleries increasingly present ceramics alongside painting and design, the fundamental question returns: when does ceramics cease to be utilitarian and begin to be collectible? The answer is not romantic. The market does not reward “age” or “prettiness.” The market rewards what can be defended: authorship, context, edition, quality, and condition.

Utilitarian versus artistic ceramics: a difference that is not always visible

In market terms, utilitarian ceramics are objects created within the logic of function: they are meant to serve, to be repeatable, to fit the table, the interior, the fashion. Artistic ceramics, by contrast, begin where function ceases to be the goal and becomes merely a point of departure. A vase no longer has to “stand straight,” a bowl need not be comfortable, and a cup may be deliberately impractical. This boundary is often subtle, because many objects balance between design and art. The market resolves it not on the basis of the owner’s declaration, but on the basis of the object’s characteristics and its “biography.”

The ceramic studio: a mark of quality and limited supply

One of the most important phenomena of the twentieth century is the rise of ceramic studios – small workshops or creative collectives that produced short series, often by hand, with a high degree of quality control. Unlike large factories, they did not operate within the logic of mass markets, but within an authorial logic. For the collector, a studio functions much like an atelier in printmaking or an edition in photography: a guarantee of limited supply. In practice, this means that an object from a studio, even if formally a “vessel,” can be valued as a work, because its repetition is not assured and documentation is often better than in industrial production.

Editions and series: when repetition builds value

The paradox of the ceramics market is that repetition can both diminish and increase price. Mass production by its nature suppresses collector uniqueness. In the artistic segment, however, editions function differently: a short, controlled series, numbered or clearly described, builds trust. The difference is fundamental: in mass production repetition means oversupply; in editions it means consciously established rarity. Therefore, in valuation it is crucial to determine whether we are dealing with:

- a unique object (one-off),

- an object from a short studio series,

- an object from industrial production,

- an object “after” a model – later, derivative, inspired.

The collectors’ market rewards the first two, tolerates the third in selected cases (when we speak of design icons), and usually relegates the fourth to the decorative segment.

Signature: a mark that must be authentic

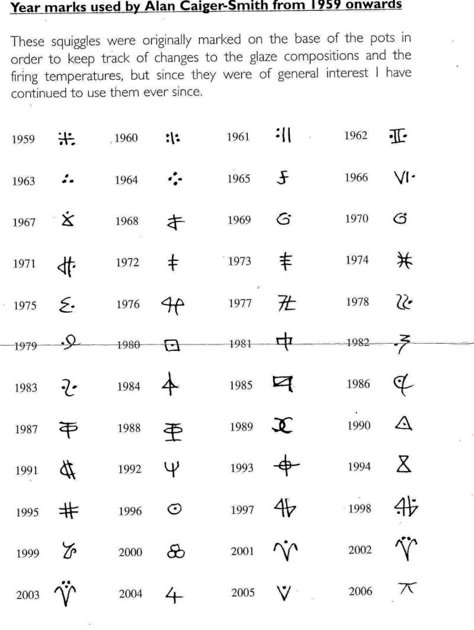

In ceramics, the signature is one of the most important elements, but also one of the most frequently misunderstood. A signature is not an automatic guarantee of value. What matters is whether it is consistent with the period, style, and technique, whether it is executed in a manner characteristic of the artist or studio, and whether it is not later. The market knows cases of added signatures, objects “boosted” with workshop marks, or erroneous attributions. In practice, one evaluates:

- the placement of the signature (base, side, underglaze, overglaze),

- the technique (incised, stamped, painted),

- consistency with other known examples,

- the presence of additional markings: mold number, edition number, date, studio mark.

A signature is strong only when it can be defended.

Technique and quality: glaze, form, the artist’s “language”

In artistic ceramics, quality does not mean “no flaws.” Sometimes controlled crazing of glaze, irregularity, kiln marks, or firing experiments are precisely what build value – provided they are intentional and characteristic. The market rewards objects that have a recognizable language: a specific glaze palette, typical proportions, a repeatable formal gesture. In other words, collectible ceramics must have “DNA” that can be recognized.

Condition: ceramics are unforgiving

Here the market is exceptionally strict. Cracks, breaks, repairs, retouching, glaze losses, amateur restorations – all of these can drastically reduce value. In ceramics, the difference between an “ideal” object and a restored one is often greater than in many other categories of antiques. Collectors pay for objects that can survive the next sale without risk.

When ceramics become collectible: the market test

In practice, twentieth-century ceramics move from the utilitarian to the collectible segment when several conditions are met simultaneously:

- they have recognizable authorship (or credible attribution),

- they come from a studio or a short series,

- they bear a signature or markings that can be verified,

- they represent a style or movement significant to the history of design or art,

- they are in good condition,

- and – most importantly – there is real demand demonstrated in transactions, not merely in asking prices.

Summary: the market pays for what can be defended

Artistic ceramics of the twentieth century are today one of the most dynamic areas of collecting, because they combine the materiality of craft with the language of art. But the valuation mechanism is ruthless: the market pays not for what is “pretty,” not for what is “old,” and not for what is “from grandmother,” but for objects that have authorship, context, quality, and credibility. The moment when ceramics cease to be utilitarian and begin to be collectible does not depend on whether they can be used. It depends on whether they can be defended.