Owners of antiques and works of art share one common tendency: they assess an object the same way they would a household item. They look at whether it “looks nice,” whether it “has no major damage,” whether it “hangs well and pleases the eye.” The market, however, looks differently. For the market, condition is not an aesthetic impression but a set of risks. And risk has a price. Sometimes so high that an object “beautiful to the eye” becomes “unacceptable” in professional trade.

That is precisely why condition is one of the most important valuation factors—and at the same time the one most frequently ignored by owners. Not out of bad faith, but because most people do not know the difference between what looks good in a living room and what meets the standards of the auction, dealer, or institutional market.

“Good condition” in the owner’s language and in the market’s language are two different things

In private terms, “good condition” usually means: not broken, not cracked, not dirty, no holes. In market terms, “good condition” means something far more precise: absence of intervention, material stability, a readable original layer, predictability of behavior over time, and conservation acceptability.

What for an owner is “refreshing” may, for the market, be a “violation of the original.” What for an owner is a “minor issue” may, for an appraiser, be a factor that changes the class of the object. And most importantly: the market does not assess whether something is “pretty.” The market assesses whether something is “safe to buy.”

Where major price differences come from in seemingly similar objects

Valuation of works of art and antiques is to a large extent a valuation of integrity. An object in original condition—even if less visually striking—may be valued higher than a “nicer” object that has undergone unsuccessful interventions. Key critical points include:

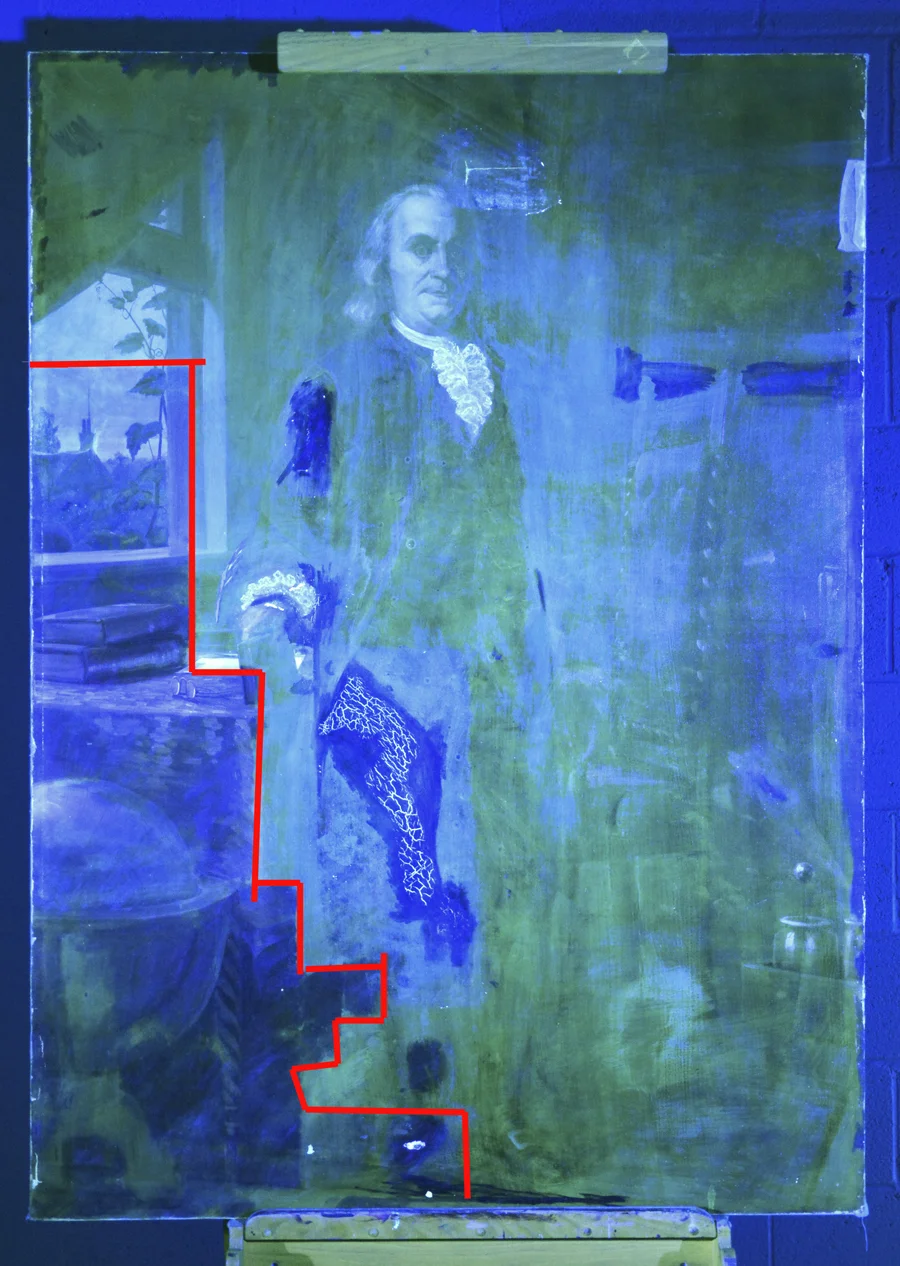

1) Retouching and overpainting

For a layperson, retouching may be invisible or even “improve” the image. For the market, it is information about interference with the original. If retouching is extensive, unprofessional, or covers significant parts of the work, the price may drop dramatically. In extreme cases, the object ceases to be treated as a full-value example and begins to function as a “conservation problem.”

2) Cleaning and “refreshing”

One of the most expensive mistakes owners make is cleaning an object themselves or entrusting it to a random “restoration.” Excessive cleaning removes glazes, alters tonality, flattens texture, and in the case of furniture or sculpture can destroy patina—that which, in antiques, forms part of their value. The market recognizes such actions faster than owners are able to accept them.

3) Cracks, losses, deformations—even if they “do not bother”

A crack in porcelain, micro-losses in gilding, warping of a panel, waviness of canvas, detachment of paint layers—these are not “cosmetic flaws.” They are signals of material stability. Institutions, galleries, and professional collectors do not buy objects that may require immediate costly intervention or will continue to deteriorate.

4) Secondary elements and lack of originality

In antiques, one principle operates with particular severity: replaced parts reduce value more than owners want to believe. Replaced veneers, new polish, added elements, secondary screws, a new mechanism in a clock—all of these create a “composite” object, and the market pays less for objects that are not coherent.

Why the market is “harsher” than the owner

The market has an advantage: it sees hundreds of similar objects. The owner sees one—his own. Therefore, owners interpret condition emotionally, while the market interprets it comparatively. If better-preserved examples or those with fewer interventions exist in trade, they set the price ceiling.

Importantly, even if an object is rare, condition still matters. Rarity may soften requirements, but it does not cancel the rules. In such cases, the market does not say, “we buy despite the condition,” but rather, “we buy, but we pay less because the risk is higher.”

“Market-acceptable” – what does it mean?

This is a key term worth introducing into valuation thinking. Market acceptability means that an object:

– has a condition defensible in professional trade (auction, dealer, private sale),

– contains no interventions that compromise originality,

– does not generate immediate conservation costs,

– has a condition report that does not deter institutional buyers,

– will not deteriorate over time—that is, it is stable.

The last point is particularly important: the market does not buy only the past. The market also buys the object’s future.

Valuation begins with condition, not with the name

Many owners begin their thinking with the artist, period, or signature. Professional valuation often begins the other way around: with condition. Because condition determines whether an object can be sold at all within a given market segment. Only then does everything else follow: attribution, provenance, demand, comparisons.

And here emerges the most important conclusion: “visually good” is a private category. “Market-acceptable” is a financial category. And valuation belongs to the latter.

If you want to know the real value of your object in the current market, check the valuation at ArtRate.art.